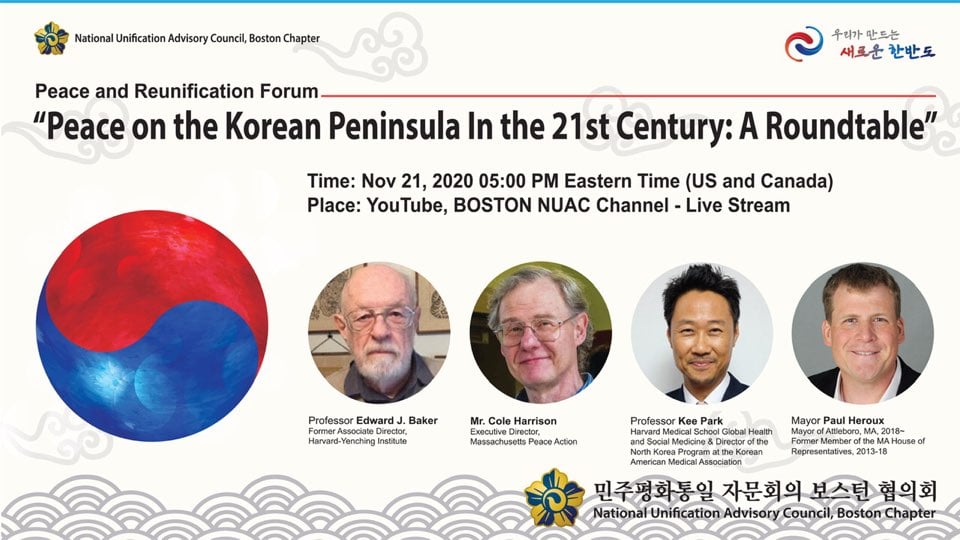

A talk presented at “Peace in the Korean Peninsula in the 21st Century”, a program sponsored by the National Unification Advisory Council’s Boston chapter, on November 21, 2020. View video of this talk at https://youtu.be/Ff3hciLUtTo

I’m Cole Harrison, executive director of Massachusetts Peace Action. We’re the state branch of the largest grassroots peace organization in the United States, and we work to abolish nuclear weapons, end US overseas interventions through wars and sanctions, and cut the Pentagon budget to help the people. We call for the United States to stop dictating the future of Korea and get out of the way of the Korean people’s desire for peace and reconciliation. I thank the National Reunification Advisory Council for inviting me to address you tonight.

Of all countries in the world, Korea has faced some of the hardest challenges in developing its national independence. As a medium sized country caught between larger and more powerful neighbors, Korea has long been subject to intervention by other powers. The quest for national unity in Korea is a thread that runs throughout its modern history, and both the South and North Korean governments are committed to the goal of reunification.

Although Korea had been a single unified kingdom for hundreds of years, it lost its independence and became a Japanese colony from 1905 to 1945. After World War II it was divided into north and south. Korea became a focal point in the cold war between the US and the Soviet Union, between capitalism and socialism. The Korean War devastated the country with hundreds of thousands of dead on both sides and millions of civilians were killed. Tens of thousands of American soldiers died also. North Korea ranks as one of the most heavily bombed countries in history, and the Korean peninsula remains heavily militarized.

The Korean War ended in 1953 with an armistice, not a peace treaty, so that the question of Korean reunification has been locked in a military confrontation since that time. The US has maintained a large military force in South Korea for 75 years; at present 28,500 US troops are deployed there on 15 different bases. Geopolitically, the US sees South Korea as a base to project US power on the Asian mainland, in opposition to Russia and China.

Under US occupation after WWII and the Korean war, the US installed politicians who had risen to prominence under Japanese rule. South Korea continued as a right wing military dictatorship for decades, and has become more democratic after bitter struggles, including the Gwangju uprising in 1980, which was put down with the assistance of the US military.

North Korea for its part tried to maintain self-reliance, or juche, rather than becoming dependent on either of its two socialist allies, the Soviet Union and China.

With the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the cold war, North Korea’s security concerns intensified. Fearing US regional military hegemony, it moved to develop a nuclear energy program starting in the 80s. North/South/US relations seesawed back and forth in the 1990s and 2000s. The Agreed Framework in 1994 called for normalization of relations, and President Kim Dae-jung’s Sunshine Policy put in place cultural exchanges, economic cooperation, and reconciliation. But the GW Bush administration ended the Agreed Framework, North Korea tested its first nuclear weapon in 2006, and conservative government in South Korea ended the Sunshine Policy. The UN has imposed severe sanctions on North Korea since 2006.

There was little progress under Obama, but in 2017 Moon Jae-in ran for president of South Korea on a platform of reinstating the Sunshine Policy, and won a decisive victory. Trump became president of the US the same year and his America First foreign policy sought to end unnecessary American foreign commitments. After threatening North Korea with “fire and fury”, Trump reversed course and met Chairman Kim Jong-un in Singapore in 2018, signing an agreement to establish a peace regime on the Korean peninsula. Presidents Moon and Kim met three times that year and agreed on a variety of confidence building measures, but progress towards peace stalled after the Trump-Kim Hanoi summit in February 2019.

Both Democrats and Republicans in Washington continue to say that North Korea must eliminate its nuclear weapons before peace and reconciliation can begin. Trump tried to redefine this dead-end policy, but his secretaries of state Bolton and Pompeo were not willing to carry it out. President-elect Biden then ran to the right of Trump in their final debate October 22, attacking Trump for meeting with Kim Jong-un before he denuclearizes, and comparing him to Hitler.

However, here’s another view. North Korea has good reason to fear US military attack. Our bombers destroyed North Korea’s cities in the 1950s, we fly nuclear bombers near Korea and conduct threatening war games, and our military is tightly integrated with South Korea’s military. In fact, the South is protected by US nuclear weapons, so it’s inaccurate to state that the North’s nuclear weapons have upset the military balance. What they have really done is make the military balance a bit closer to equal, and the North is struggling to use the breathing room it gained to develop its economy and improve the lives of its people. The military confrontation is preventing political progress even though both South and North Koreans want reconciliation and a peace treaty to end the Korean war.

The forward US position in Korea is a relic of the Cold War, perpetuated by ossified thinking in Washington. It only makes sense in the context of US empire, in which the US seeks to maintain its position as the dominant power throughout the world. But now, thirty years after the end of the first Cold War, the US is moving towards a dangerous new cold war with China, political, economic, and military. The US presence in Korea is now a part of US military moves to encircle China with a chain of alliances and bases stretching from India through Vietnam, Japan, and Korea. Biden helped develop this encirclement in the Obama administration, and now that Trump has moved towards decoupling the US and Chinese economies, he will face the temptation to further mobilize US power against China. Korea is likely to be caught in the middle of this deteriorating regional situation.

So, is there a basis for a movement in the United States to end the Korean war? I think there is. The impasse on the Korean peninsula cannot last forever. It frustrates the national aspirations of the Korean people, who need to put division behind them and move towards reconciliation. And from the point of view of most ordinary people in the US, why should the US be so deeply committed in Korea? The US would immediately be drawn into any war that started there. American casualties, both soldiers and civilians, would mount, and use of nuclear weapons would be a serious danger.

We’ve already seen US military spending rise rapidly during the Trump administration, from $767 billion in 2016 to $936 billion in 2020. Yet the US economy is being hollowed out and we need that money at home to provide jobs, healthcare, housing, education and a clean environment to the American people. So it would be more than prudent for America to get out of the way of peace negotiations between Koreans and follow their lead towards a demilitarized Korea. We need to defund the Empire, bring US troops home, and stop interfering with the Korean people’s aspirations for national reconciliation.

These ideas are gaining traction in the political mainstream. Massachusetts Peace Action participates in the Massachusetts Korea Peace Campaign, which is an affiliate of the Korea Peace Now Grassroots Network. We work with Rep. Ro Khanna who has introduced a resolution in Congress calling for an end to the Korean War. That bill, H.Res.152, now has 51 cosponsors in the House of Representatives, including Representatives Jim McGovern and Ayanna Pressley from Massachusetts. We have met with the staffs of all Massachusetts members of Congress asking for their support and we are hopeful that we will make even more progress next year. We also support a relaxation to sanctions, an end to US military exercises in South Korea, and an end to the ban on travel to North Korea.