by Joseph Gerson

originally published in CommonDreams

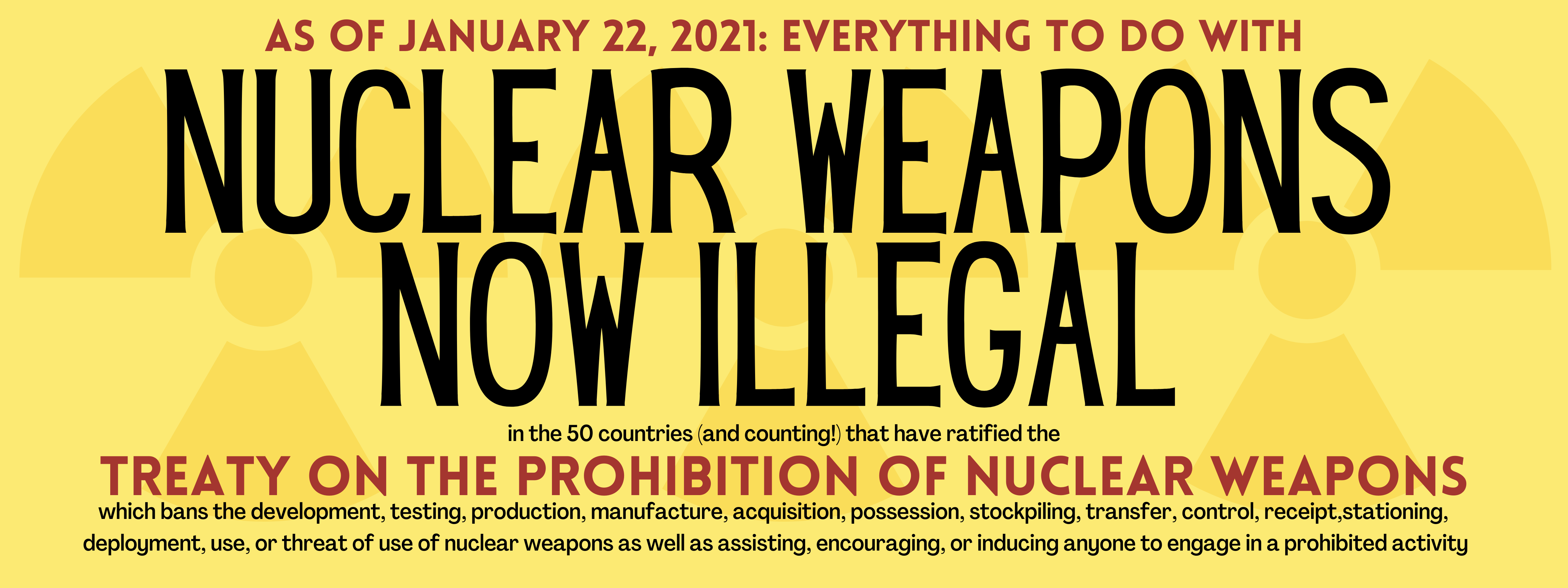

On Friday, January 22, people in cities and towns across in the United States and around the world, will celebrate the entry into force of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).

Those gathering, online and elsewhere, stand in sharp contrast with the electric sense of fear felt by policy makers and others that President Trump might push the nuclear button in the immediate aftermath of his failed coup. With President Trump facing possible criminal conviction and terminal bankruptcy, and having the power to initiate nuclear war on his own authority, Nancy Pelosi had good reason to press the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, General Milley, to ensure that the president couldn’t take us all with him as he went down. For several days, headlines focused on the danger of nuclear war, which should facilitate arms control and disarmament advocacy in coming months.

On at least 24 occasions, U.S. presidents have prepared and/or threatened to initiate nuclear war.

For decades, absent such desperate circumstances, many world leaders and policy makers have understood that accidents and miscalculations—including the belief the nuclear war can be fought and won—could lead to nuclear catastrophe and urged action to eliminate nuclear weapons. A year before President Kennedy and Soviet Premier Khrushchev went “eyeball to eyeball” during the Cuban Missile Crisis, speaking from the dais of the U.N. General Assembly, Kennedy warned: “Every man, woman and child lives under a nuclear sword of Damocles, hanging by the slenderest of threads, capable of being cut at any moment by accident or miscalculation or by madness.” The weapons of war, he urged “must be abolished before they abolish us.”

Since that day, during international crises and wars—on at least 24 occasions—U.S. presidents have prepared and/or threatened to initiate nuclear war. Similarly, leaders of each of the eight other nuclear powers has made similar threats at least once. Human survival indeed hangs from the slenderest of threads, a reality confirmed by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists expert panel who have set their Doomsday Clock at 100 seconds to midnight, the closest to catastrophe since the clock was created in 1953 at the height of the Cold War.

During the 75 years since the unnecessary and functionally criminal indiscriminate atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, A-bomb survivors, scientists and physicians, scholars, community-based activists, diplomats and many national leaders have worked to prevent apocalypse and to create a nuclear weapons-free world.

A high point came in 1970 when, after years of protests, diplomacy and negotiations, the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty came into effect. This seminal treaty was a grand bargain made between the nuclear haves and have nots. In exchange for the non-nuclear weapons states foreswearing development or possession of nuclear weapons, the nuclear powers recognized their right to generate nuclear power for peaceful purposes (a mistake) and, in article XI, committed to engage in good faith negotiations for the complete elimination of their nuclear arsenals.

Refusing to compromise their omnicidal power and bowing to the interests of their respective military-industrial complexes, the “good faith” negotiations never occurred. India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea have since become nuclear powers, thus increasing the threats to human survival. Quantitative and qualitative nuclear arms races also followed, with the United States now on track to spend $2 trillion (an unimaginable sum) to replace its entire nuclear arsenal and its delivery systems.

Concerned about the prospects for human survival, and with the nuclear powers refusing to take meaningful steps year after year to fulfill their Article VI commitment, countries as diverse as Sweden, South Africa, Ireland and Mexico sought a means to break through the nuclear powers’ rationale; that national security concerns and the need to maintain nuclear deterrence required the maintenance of “modernization” of their nuclear arsenals. In 2013 the non-nuclear weapons states found their way to the obvious alternative paradigm: what nuclear weapons do to people.

The first of three Humanitarian Consequences of Nuclear Weapons conferences, held in Oslo that year, diplomats from 127 nations and civil society activists gathered to learn what nuclear weapons actually do and the dangers they represent. At the second conference, held the following year in Nayarit, Mexico, with all the nuclear powers absent except North Korea, conference organizers felt free to begin the conference with the testimonies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki A-bomb survivors. They described their suffering, losses, and the literal “Hell on earth” that they had witnessed, and they repeated their fundamental truth that “Human beings and nuclear weapons cannot coexist.” Power point presentations by representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross and Chatham House in London demonstrated why no institution can meaningfully respond to the massive death and destruction inflicted by a single nuclear weapons detonation in a city.

The most telling moment in Nayarit came when, after hearing these testimonies and details about nuclear weapons “modernizations” and warfighting doctrines, a young African diplomat rose. With his pleading arms outstretched, he cried out “What are these people thinking?”

The outcome of the third and final Humanitarian Consequences conference, held in Vienna in December, 2014, was sealed shortly after it began. Following opening statements came the testimonies by a courageous Hiroshima survivor and an Australian Maori who described the deadly impacts of uranium mining. These framed the conference, but the coup de grace came from a woman who was assisted onto the stage in her wheelchair. Beginning with a heartrending cry that “My government has killed me” and in her passionate and unscripted speech, she explained how fallout from nuclear weapons testing (underground as well as atmospheric) had sickened her with cancer and taken the lives of many patriotic citizens of St. George, Utah. No one in the Palace hall was left unmoved, and the pathetic rebuttal by the U.S. ambassador was painfully embarrassing to all.

Following speech after speech by the assembled diplomats, the conference closed with the Austrian government’s pledge, joined by nearly all of the participating states. It reiterated the risks posed by nuclear weapons, described what it termed as the “legal gap for the prohibition and elimination of nuclear weapons” that must be filled (i.e. a means to hold the nuclear powers accountable to Article VI of the NPT, and urged governments to join Austria in taking action to reduce the dangers of nuclear war).

That appeal led to the convening in 2017 of negotiations at the United Nations which concluded with the promulgation of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons by 122 governments—none of them nuclear weapons states.

There are no guarantees that the TPNW will move any of the nuclear powers, all of which are spending vast fortunes to upgrade their nuclear arsenals and delivery systems, and whose political systems are deeply influenced by their military-industrial complexes.

Having secured the necessary ratifications, the Treaty enters into Force on January 22, 2021. While opposed by the nuclear weapons states and their military allies, the Treaty further undermines the legitimacy of nuclear weapons and is designed to reinforce the NPT. It prohibits the development, production, manufacture, acquisition, possession, stockpiling, transfer, stationing, installation, and the threat to use nuclear weapons. Among its most important articles are those that forbid non-nuclear weapon states to assist the nuclear activities of the nuclear powers, for example refueling nuclear-capable bombers, the mandate to assist nuclear weapons victims, and the requirement that Treaty nations “encourage States not party to this Treaty to sign, ratify, accept, approve or accede to the Treaty.” “Encouragement” could take many forms: lobbying government officials, funding nuclear disarmament advocates, discouraging investments from corporations and financial institutions involved in the production of nuclear weapons. Ultimately, even sanctions!

There are no guarantees that the TPNW will move any of the nuclear powers, all of which are spending vast fortunes to upgrade their nuclear arsenals and delivery systems, and whose political systems are deeply influenced by their military-industrial complexes. The authors of the Prohibition Treaty understand that there are no short cuts to universalizing adherence to the treaty. They know that road to nuclear weapons-free world is a long and difficult one.

While activists in the United States take inspiration and encouragement from the TPNW, over the next several years, the most critically important campaigning will be in the so-called “umbrella states.” These are the NATO nations, others in the Asia-Pacific, and the Russian dominated Commonwealth of Independent States, functionally protectorates that rely on the U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals. Should one or more of these dependent states break ranks by signing and ratifying the Treaty, it will threaten to unravel the political fabric of the world’s nuclear disorder.

That possibility is not farfetched. A massive majority of Japanese want their government to sign the TPNW. Australia’s Labor Party, which was narrowly defeated in the country’s 2019 election, is committed to signing the treaty. And in the Netherlands a parliamentary majority voted in favor on the Treaty.

Those of us here in the United States who have confronted the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons and understand the urgency of nuclear disarmament have our own work cut out for us. In addition to doing all that we can to preserve constitutional democracy, to stanch the pandemic, and support revitalization of our economy, we can hold President Biden’s feet to the fire. He has pledged to extend the New START Treaty with Russia, due to expire in February, and to rejoin the JCPOA nuclear deal with Iran. Biden previously stated his opposition to the U.S. “first use” nuclear warfighting doctrine that could lead to miscalculations and “use them or lose them” missile launches by U.S. rivals. With Senator Markey and others in Congress urging a no first use policy, we should be encouraging our president to spend his political capital to ensure human survival.

And, as we look for the funds to revitalize our pandemic ravaged economy, we should be encouraging the president (and Congress) to act on his doubts about the value of replacing U.S. ground-based ICBMs and standoff cruise missiles which undermine rather than augment our real security.

The TPNW provides an encouraging opening. Human survival could well depend on taking advantage of it.